By Stephanie Roman from Public Source

Ninety percent of car crashes are preventable.

Ninety percent of car crashes are preventable.

As it stands, about 30,000 people die in car crashes every year in the United States, said Mark Kopko of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation [PennDOT]. “If you could reduce that by 90 percent, that’s huge.”

Autonomous cars have the capacity to do that.

In Allegheny County, that could mean a vast reduction in the roughly 12,000 crashes in 2014 — especially of those attributed to driver error, like drunk or distracted driving and speeding.

The technology isn’t a distant dream. Much of it is being researched and designed here in Pittsburgh.

Ride-sharing app company Uber and Carnegie Mellon University [CMU] announced a partnership to work on autonomous cars a year ago. Uber set up an Advanced Technologies Center in Pittsburgh, where they have access to CMU’s talent as well as its National Robotics Engineering Center.

The cars could reduce congested parking and allow commuters to prepare for work. Eventually, they might even provide people unable to drive with access to safe and reliable transportation from their doorsteps.

But Pittsburgh’s varied weather, the resulting pothole problem and the city’s erratic streets may throw up roadblocks for these smart cars. And, the overall safety of pedestrians, bicyclists and other motorists is already a concern without the added factor of cars governed by nascent technology.

Figuring out how to legislate a cutting-edge technology poses another challenge. Some states have passed regulations creating safety measures for the testing of autonomous cars, but not Pennsylvania.

A state workgroup is making preparations to be ready for self-driving cars by the year 2040.

“There’s still too many questions and the potentials are there, so that’s the beauty,” said Kopko, PennDOT manager of traveler information and advanced vehicle technology.

The car decides

In 2013, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration defined five stages of vehicle autonomy, with level 0 being that the driver has full control of steering, brakes and throttle, and level 4 meaning that the car performs all functions independently.

In 2013, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration defined five stages of vehicle autonomy, with level 0 being that the driver has full control of steering, brakes and throttle, and level 4 meaning that the car performs all functions independently.

Some commercial vehicles are already considered levels 1 and 2, with functions like automatic braking, adaptive cruise control and self-parking.

But there’s much to be achieved before level-4 cars chauffeur people around town.

Fully autonomous vehicles need to cover two domains: highway driving and urban driving.

“Technologically, we’re pretty much there in terms of highway driving,” said John Dolan, principal systems scientist at CMU’s Robotics Institute. The demands of urban driving are “problematic,” he continued. “Nobody’s really claiming they’ve solved it.”

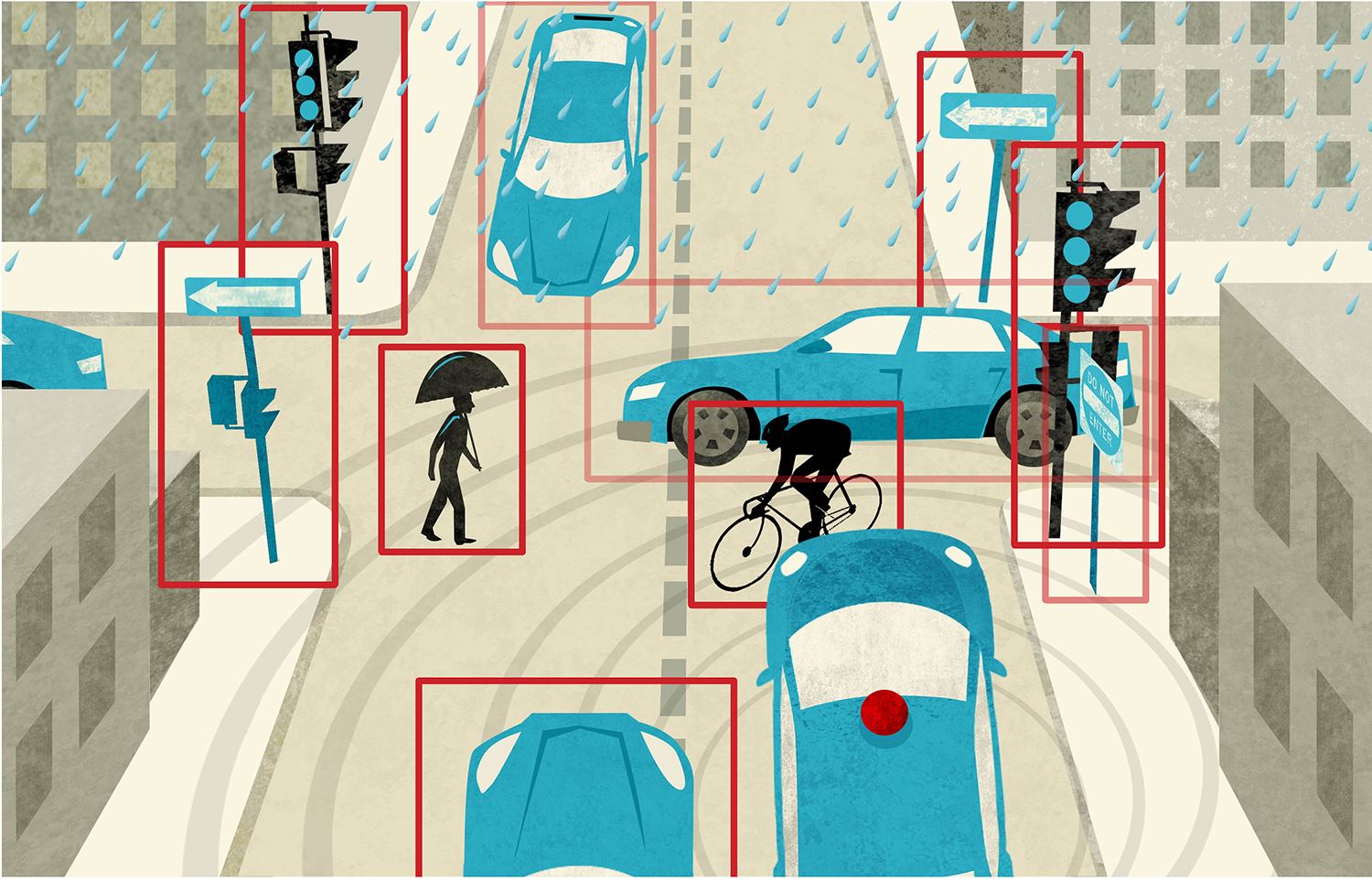

There are three major fields when it comes to teaching cars to drive themselves: perception, behaviors and motion planning.

Perception is how the cars see. They do that with sensors, like cameras, lasers testing distance, and radars detecting speed.

Behaviors are how the car makes tactical decisions, like choosing to merge into the Fort Pitt Tunnel or moving ahead at a stop sign.

Motion planning is the time the car has to make those decisions. It’s the most difficult aspect to design. While a car's sensors would be able to detect if a deer leapt out unexpectedly, it still may not be able to avoid a collision.

Many automakers are working on models of autonomous cars, and liability is a major concern.

“There’s reliability issues. Kind of like NASA and the space industry, they’re going to test it rigorously over the course of several years,” Dolan said. “They need redundancy.”

The cars also need massive computing power, which Dolan said may be the most expensive feature.

It’s likely that the first autonomous cars on the market will be luxury vehicles, and the costs will increase from there. Dolan estimated prices will start at about $60,000 to $75,000.

Street talk

Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk says his company will have autonomous cars road-ready in about two years.

Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk says his company will have autonomous cars road-ready in about two years.

Some autonomous car and tech developers say city planners shouldn’t get carried away with changes to infrastructure to make way for these cars as their capabilities will continue to evolve.

Certain changes would help, though. Cities, including Pittsburgh, may need to consider standardizing traffic signals and redesigning “problem intersections.”

For example, bizarre on-ramps, traffic lights and one-way signs between Bedford Avenue, Crosstown Boulevard and I-376 in the Hill District could confuse car computers just as much as they do humans — unless it’s been extensively mapped.

Another improvement would be to install dedicated short-range communication in traffic lights, which would signal cars when to go or slow down.

Cooperation among states may also be needed.

“There’s a huge amount of variations on [street] signs between states,” said Blaine Leonard, program manager for intelligent transportation systems at the Utah DOT. “We need to do a better job of figuring out how to make those more consistent.”

PennDOT doesn’t have major investments planned, although the agency is staying abreast of the technology. Eventually, it may look at reducing lane width or cutting out interstate lanes entirely.

One suggestion in PennDOT’s 2040 outline is to reduce the width of the Squirrel Hill tunnel lanes to 10 feet, and to add a third 9-foot lane for autonomous cars.

Kopko said the only near-term project would involve line painting.

“Some [vehicles] look at lines and some don’t,” he said.

Leonard added that white line paint isn’t as visible at night or in inclement weather, and it fades. One solution, he said, might be to put radio frequency identification, known as RFID, in the line paint.

If autonomous cars truly revolutionize the way people get around, what happens to all the parking?

“Because of the way that they circulate, the demand for parking may go down in the city. Those types of vehicles may park on the fringes for free or for cheap,” said Justin Miller, a senior planner for the city of Pittsburgh.

Miller said planners may have to consider making new parking structures adaptable, in case they become unneeded.

PennDOT agrees.

“In an urban setting, the amount of parking garages could be potential green space,” said Kurt Myers, deputy secretary of PennDOT driver and vehicle services.

Legislating the unknown

Legislating autonomous vehicles is a hurdle because of the liability involved.

“[The government willl] start to or need to get involved from a safety perspective, at least to make sure this stuff is deployed responsibly,” said Dean Pomerleau, an adjunct robotics professor at CMU and pioneer of self-driving technology. “And despite whatever Elon Musk and the tech guys say, there will be crashes.”

California and a handful of other states have enacted regulations permitting autonomous vehicle testing on public roads and establishing baseline safety measures — primarily that licensed drivers need to be in the car to take control if necessary.

In January, President Barack Obama and U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx announced they would pump $4 billion into autonomous car development over the next decade.

Foxx said the proposal will ease legislative and financial obstacles for auto and tech companies developing the cars.

PennDOT formed the Pennsylvania Connected and Automated Vehicle Working Group in 2012. It includes lawyers and representatives from the Turnpike Commission, the Federal Highway Administration and CMU.

The 2040 outline is the most official item on the books right now. There are no state regulations regarding autonomous cars in place.

With the rate of car turnover, Leonard, of the Utah DOT, said it could take 40 years for autonomous cars to become the norm.

“Even when autonomous vehicles are available and in operation, it will be a long time before they are fully integrated,” Myers said.

Removing a barrier

Autonomous cars will need a licensed driver in the seat — at least at first. But someday people who are unable to drive on their own could have the same access to cars.

Peri Jude Radecic, CEO of the Disability Rights Network of Pennsylvania, said this could be life-changing for people with disabilities.

“In rural areas, the problems are magnified, so having another transportation option available to us would be a great advance forward,” she said.

Radecic said transportation departments and the government should ensure autonomous cars are developed in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“It would save a lot of money and headaches down the road if we’re able to have these conversations ... now,” she said.

Many experts say that, like an Uber, autonomous vehicles will probably be available to order as taxis at first. They could become a choice alternative for people who live too far from their bus stop to walk or bike, but still want to be economical about transport.

“This really has the potential to impact the quality of life from a mobility standpoint for individuals literally across the world,” Myers said.

Leonard thought about how it could change his and his cohort’s future.

“I really think for [the Baby Boomer] generation the driverless car thing is really going to make it possible to participate in society when we can’t be driving,” he said.

The dream for many involved in the development of autonomous cars is that people without licenses will be able to get around without having to rely on friends or public transportation.

“It may very well be where people look back and say, ‘How archaic it is that you had to sit behind a wheel,’” Myers said.

Reach PublicSource reporter Stephanie Roman at sroman@publicsource.org. Follow her on Twitter @ShogunSteph. Read the original article here.